A grand piano has a mind-numbing number of adjustments well beyond that of tuning.I’m not sure what the actual mechanical differences are in piano actions, but as a player, it is VERY apparent there ARE significant ones . For me, and most studio players I know, Yamaha is the desired piano to cut with. It not only provides for good feel, but it is very consistent from piano to piano. Important for session players that hop from studio to studio.

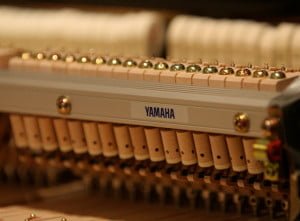

Recording a grand piano is perhaps the most complex instrument an engineer will encounter. And much like a drum-kit, the sound of the instrument is critical. A typical piano tech would consider voicing the consistency between notes up and down the piano. But for recording, voicing becomes a very complex set of needs. The sound from a grand piano doesn’t emanate where you would think. A lot of engineers mic the strings right above the hammer. This is typically done it an effort to get the piano more percussive and help it cut through a pop track.Unfortunately, most of what occurs where the hammer strikes the strings, is noise – literally. The closer a mic is to the action, the more likely squeaks and wood knocks will be heard. Don’t get me wrong, this is part of the magic of a real instrument. But since the volume of sound is actually vibration rising from the sound board, and bridge, the largest sonic difference comes from changing the surface of the item striking the string. Think of it this way: Using a soft tympani mallet to strike a drum will produce a duller sound. No amount of positioning the mic will every make it “smack” like changing to a 5A drumstick.Unfortunately, hammers can’t be swapped out easily. So simple lacquering the hammers (like the ole’ days) will get you that pop sound…but that’s all you’ll get. Next time your in session and the player is recording Chopin or Brahms, you going to be knocking everything above 2K off.

A lot of piano techs have moved from lacquer to chemistry because of this. Chemistry allows the change to occur deeper in the hammer, opposed to the surface. I’ve played many of these, and some are very good. But again, it tends to pigeonhole the piano into a certain sound.The solution that Yamaha International provided was to not alter the hammers fabric, but to reduce it. Sounds crazy, I know. And watching the Yamaha tech file gently away for days on the hammers…I had my doubts. In the end, what it provided was a piano with outstanding dynamics. Played softly, the sound is very warm and inviting. It produces enough volume for a good recording, but can remain very mellow and gentle. Played more aggressively, the piano produces an exponentially brighter sound. And at full volume almost sizzles.The last facet of voicing for the studio is the Yamaha sound itself. Bosendorfer, Steinway, and even Kawai are each undeniable in my mind as a producer. But Yamaha provides a very generic tone that demands you listen to the playing, not the instrument. I guess, in a way, that’s its signature sound.

Yep, even the acoustic grand needs to interface electronically in today’s studios. Enter Yamaha’s Disklavier package.The Disklavier was originally designed for the consumer – essentially as a player piano. It evolved into a Karaoke package that would let owners play along with recordings. In the third incarnation, it became a MIDI aware instrument.Ours is equipped with the Disklavier Mark IV, whose resolution transformed the Disklavier equipment into a professional instrument. This essentially allows the wonderful aspect of MIDI to join with the feel and sound of an acoustic grand.

A grand piano has a mind-numbing number of adjustments well beyond that of tuning.I’m not sure what the actual mechanical differences are in piano actions, but as a player, it is VERY apparent there ARE significant ones . For me, and most studio players I know, Yamaha is the desired piano to cut with. It not only provides for good feel, but it is very consistent from piano to piano. Important for session players that hop from studio to studio.

A grand piano has a mind-numbing number of adjustments well beyond that of tuning.I’m not sure what the actual mechanical differences are in piano actions, but as a player, it is VERY apparent there ARE significant ones . For me, and most studio players I know, Yamaha is the desired piano to cut with. It not only provides for good feel, but it is very consistent from piano to piano. Important for session players that hop from studio to studio. Recording a grand piano is perhaps the most complex instrument an engineer will encounter. And much like a drum-kit, the sound of the instrument is critical. A typical piano tech would consider voicing the consistency between notes up and down the piano. But for recording, voicing becomes a very complex set of needs. The sound from a grand piano doesn’t emanate where you would think. A lot of engineers mic the strings right above the hammer. This is typically done it an effort to get the piano more percussive and help it cut through a pop track.Unfortunately, most of what occurs where the hammer strikes the strings, is noise – literally. The closer a mic is to the action, the more likely squeaks and wood knocks will be heard. Don’t get me wrong, this is part of the magic of a real instrument. But since the volume of sound is actually vibration rising from the sound board, and bridge, the largest sonic difference comes from changing the surface of the item striking the string. Think of it this way: Using a soft tympani mallet to strike a drum will produce a duller sound. No amount of positioning the mic will every make it “smack” like changing to a 5A drumstick.Unfortunately, hammers can’t be swapped out easily. So simple lacquering the hammers (like the ole’ days) will get you that pop sound…but that’s all you’ll get. Next time your in session and the player is recording Chopin or Brahms, you going to be knocking everything above 2K off.

Recording a grand piano is perhaps the most complex instrument an engineer will encounter. And much like a drum-kit, the sound of the instrument is critical. A typical piano tech would consider voicing the consistency between notes up and down the piano. But for recording, voicing becomes a very complex set of needs. The sound from a grand piano doesn’t emanate where you would think. A lot of engineers mic the strings right above the hammer. This is typically done it an effort to get the piano more percussive and help it cut through a pop track.Unfortunately, most of what occurs where the hammer strikes the strings, is noise – literally. The closer a mic is to the action, the more likely squeaks and wood knocks will be heard. Don’t get me wrong, this is part of the magic of a real instrument. But since the volume of sound is actually vibration rising from the sound board, and bridge, the largest sonic difference comes from changing the surface of the item striking the string. Think of it this way: Using a soft tympani mallet to strike a drum will produce a duller sound. No amount of positioning the mic will every make it “smack” like changing to a 5A drumstick.Unfortunately, hammers can’t be swapped out easily. So simple lacquering the hammers (like the ole’ days) will get you that pop sound…but that’s all you’ll get. Next time your in session and the player is recording Chopin or Brahms, you going to be knocking everything above 2K off. A lot of piano techs have moved from lacquer to chemistry because of this. Chemistry allows the change to occur deeper in the hammer, opposed to the surface. I’ve played many of these, and some are very good. But again, it tends to pigeonhole the piano into a certain sound.The solution that Yamaha International provided was to not alter the hammers fabric, but to reduce it. Sounds crazy, I know. And watching the Yamaha tech file gently away for days on the hammers…I had my doubts. In the end, what it provided was a piano with outstanding dynamics. Played softly, the sound is very warm and inviting. It produces enough volume for a good recording, but can remain very mellow and gentle. Played more aggressively, the piano produces an exponentially brighter sound. And at full volume almost sizzles.The last facet of voicing for the studio is the Yamaha sound itself. Bosendorfer, Steinway, and even Kawai are each undeniable in my mind as a producer. But Yamaha provides a very generic tone that demands you listen to the playing, not the instrument. I guess, in a way, that’s its signature sound.

A lot of piano techs have moved from lacquer to chemistry because of this. Chemistry allows the change to occur deeper in the hammer, opposed to the surface. I’ve played many of these, and some are very good. But again, it tends to pigeonhole the piano into a certain sound.The solution that Yamaha International provided was to not alter the hammers fabric, but to reduce it. Sounds crazy, I know. And watching the Yamaha tech file gently away for days on the hammers…I had my doubts. In the end, what it provided was a piano with outstanding dynamics. Played softly, the sound is very warm and inviting. It produces enough volume for a good recording, but can remain very mellow and gentle. Played more aggressively, the piano produces an exponentially brighter sound. And at full volume almost sizzles.The last facet of voicing for the studio is the Yamaha sound itself. Bosendorfer, Steinway, and even Kawai are each undeniable in my mind as a producer. But Yamaha provides a very generic tone that demands you listen to the playing, not the instrument. I guess, in a way, that’s its signature sound. Yep, even the acoustic grand needs to interface electronically in today’s studios. Enter Yamaha’s Disklavier package.The Disklavier was originally designed for the consumer – essentially as a player piano. It evolved into a Karaoke package that would let owners play along with recordings. In the third incarnation, it became a MIDI aware instrument.Ours is equipped with the Disklavier Mark IV, whose resolution transformed the Disklavier equipment into a professional instrument. This essentially allows the wonderful aspect of MIDI to join with the feel and sound of an acoustic grand.

Yep, even the acoustic grand needs to interface electronically in today’s studios. Enter Yamaha’s Disklavier package.The Disklavier was originally designed for the consumer – essentially as a player piano. It evolved into a Karaoke package that would let owners play along with recordings. In the third incarnation, it became a MIDI aware instrument.Ours is equipped with the Disklavier Mark IV, whose resolution transformed the Disklavier equipment into a professional instrument. This essentially allows the wonderful aspect of MIDI to join with the feel and sound of an acoustic grand.